COVID-19 Symptoms Tracker

March 24, 2020

David Nunan, Jon Brassey, Kamal Mahtani, Carl Heneghan, Hopin Lee, Jamie Hartmann Boyce, Antoni Gardner, Maia Patrick-Smith

On behalf of the Oxford COVID-19 Evidence Service Team

Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences,

University of Oxford

Translated in Portuguese by Carolina de Oliveira Cruz Latorraca, Rafael Leite Pacheco, Ana Luiza Cabrera Martimbianco, Oxford-Brazil EBM Alliance

UPDATE 16th JUNE:

On the 20th May we posted findings from our searches up to 18 May in relation to loss of smell (anosmia) and taste (ageusia) following the announcement by the UK government of the addition of these two symptoms that should warn people to self-isolate for 7 days.

We are currently reviewing over 40 identified systematic reviews. Reviews are being assessed for their methodological quality, identification of unique and duplicate studies, quality of included studies, pooled estimates of symptom prevalence and prevalence of comorbidities. We are also attempting to extract information regarding cases of single and multiple symptoms in patients with COVID where possible. We appreciate your patience as we undertake this work.

UPDATE 29th MARCH:

We have updated our main figure posted originally on 27th March to now include the following additional information:

- The published date of the latest version

- The number of participants

- A note that the data are based on data that has not yet been peer-reviewed

- A URL link to this webpage

- Relevant logos

We will provide updates of changes to the figure based on emerging data and any changes to the existing data as and when we have them.

UPDATE 27th MARCH:

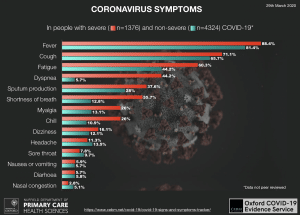

Our search has revealed six systematic reviews providing relevant information on signs and symptoms COVID-19. 3/6 of these reviews are preprints and 1/6 is in children only. The most recent review in adults (preprint 20 March) was retrieved on 25 March and provides pooled data on signs and symptoms in 5700 individuals with confirmed severe (n=1374) and non-severe (n=4326) cases of COVID-19.

IMPORTANT NOTE: The following data are from a preprint study and have not been peer-reviewed. It reports new medical research that has yet to be evaluated and so should not be used to guide clinical practice.

|

Clinical symptoms (%)

|

People with severe* COVID-19

|

People with non-severe COVID-19

|

|

Fever

|

88.4% |

81.4% |

|

Cough

|

71.1% |

65.7% |

|

Fatigue

|

60.3% |

44.2% |

|

Dyspnea

|

44.2% |

5.7% |

|

Sputum production

|

37.6% |

28% |

|

Shortness of breath

|

35.7% |

12.8% |

|

Myalgia

|

26% |

13.1% |

|

Chill

|

26% |

10.9% |

|

Dizziness

|

16.1% |

12.1% |

|

Headache

|

11.3% |

13.5% |

|

Sore throat

|

7.8% |

9.7% |

|

Nausea or vomiting

|

5.9% |

5.7% |

|

Diarhoea

|

5.7% |

5.8% |

|

Nasal congestion

|

2.8% |

5.1% |

|

*Severe disease was defined as meeting one of the following criteria: 1) presence of shortness of breath with a respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/minute; 2) an oxygen saturation (SpO2) ≤ 93% in the resting state; 3) hypoxemia defined as an arterial partial pressure of oxygen divided by the fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2 ratio) ≤ 300 mmHg; 4) presence of radiographic progression, defined as ≥ 50% increase of target lesion within 24-48 hours. The criterion was based on the Chinese COVID-19 prevention and control program (6th edition, http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/8334a8326dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2.shtml, accessed Feb 18, 2020) and American Thoracic Society guideline2

Source: Xianxian Zhao, Bili Zhang, Pan Li, Chaoqun Ma, Jiawei Gu, Pan Hou, Zhifu Guo, Hong Wu, Yuan Bai. Incidence, clinical characteristics and prognostic factor of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis medRxiv 2020.03.17.20037572; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.17.20037572.

24th MARCH:

Why a symptom tracker?

A better understanding as to the signs and symptoms will help both health services and members of the public make informed decisions in relation to COVID-19. Available information currently only offers a snapshot of common signs and symptoms but fails to adequately report additional much-needed information to help reduce uncertainty. For example, are signs and symptoms similar in people of different ages, with existing or past health conditions, medication use and across different settings or countries?

What we are doing?

To help offer some clarity, we are performing a living review of available systematic reviews and individual case-reports/series that provide aggregated data on signs and symptoms and including important additional information where possible. The review of evidence will form the basis of a living symptom tracker that will be regularly updated as new evidence emerges.

What next?

Once collated, we will share our findings via a Google sheet dataset. If you are aware of any relevant datasets/publications/prepublications providing or assessing signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and are willing to share them please email Dr David Nunan: david.nunan@phc.ox.ac.uk

The Evidence COVID-19 Service is supported by the NIHR SPCR Evidence Synthesis Working Group [Project 390]

Project team

David Nunan is a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford. He is also an Editor at the BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine journal and Director of PG Certificate in Teaching Evidence-Based Health Care

Jon Brassey is the Director of Trip Database Ltd, Lead for Knowledge Mobilisation at Public Health Wales (NHS) and an Associate Editor at the BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine

Kamal R. Mahtani is a GP, Associate Professor and Deputy Director of the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford. He is also an Associate Editor at the BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine journal and Director of The Evidence-based Healthcare MSc in Systematic Reviews

Carl Heneghan is the Editor in Chief BMJ EBM and Professor of EBM, Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford

Hopin Lee is an NHMRC postdoctoral research fellow at the Centre for Statistics in Medicine at the Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford.

Jamie Hartmann-Boyce is a departmental lecturer and deputy-director of the Evidence-Based Health Care DPhil programme within the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine in the Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences, University of Oxford.

Antoni Gardener is an interim foundation year doctor at the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust deployed early to combat the COVID-19 crisis. Antoni’s interests lie in evidence-based surgery and medical education.

Maia Patrick-Smith is a 5th-year medical student at Pembroke College at the University of Oxford.

Disclaimer: the article has not been peer-reviewed; it should not replace individual clinical judgement and the sources cited should be checked. The views expressed in this commentary represent the views of the authors and not necessarily those of the host institution, the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. The views are not a substitute for professional medical advice.

Search strategy

We are conducting a search of PubMed for systematic reviews and conduct scans of LitCovid and MedRxiv for relevant reprints every two weeks. We screen the PHE International Epidemiology Daily Evidence Briefing daily for articles related to signs and symptoms. In addition, potentially relevant papers identified via Twitter are also screened. Data from studies published in languages other than English were not included.

PubMed search string: (coronavirus OR COVID19) AND (clinical presentation OR signs OR symptoms OR features OR manifestations) Filters: Systematic Reviews

Data extraction

For each included systematic review, data are extracted to a Google spreadsheet on the following items; publication date, the end search date, if the study is peer-reviewed, country of origin based on corresponding author affiliation(s), population, number of studies, number of participants, designs of included studies, the origin of included studies, if a pooled estimate is provided.

The methodological quality of the included reviews is assessed using AMSTAR-2.

Primary studies within included reviews are cross-checked for duplication to determine the number of unique studies in the systematic review evidence-base.

Additional data are then extracted from the most up-to-date, highest quality systematic reviews for specific populations (adults [>17 yrs] or children, pregnant) as follows: if reviewers performed quality assessments and the results of these are presented, setting (hospital, community, other), subgroups presenting data, sample size, age, % female, clinical symptoms (based on pooled estimates with 95% confidence intervals if given), comorbidities (based on pooled estimates with 95% CI if given). Important additional information was extracted where available including: if the review authors extracted information on proportions of people with combinations of symptoms e.g. fever alone, Fever & cough but no shortness of breath; if the review authors extracted information on definitions of symptoms or criteria for how these were determined e.g. severity, criteria for fever, dysonoea or shortness of breath.