Loss of smell and taste as symptoms of COVID-19: what does the evidence say?

May 20, 2020

David Nunan

Lay Summary by Mandy Payne, Health Watch

The author leads the University of Oxford Teaching Evidence-Based Health Care programme

On Monday 18 May the UK Government added loss of smell (anosmia) and taste (ageusia) to the list of symptoms of coronavirus infection that should warn people to self-isolate for 7 days. Until now, only fever and cough were triggers for people to isolate, in case they had and could spread the infection.

So why the addition of this symptom now? The Government’s website states: “We have been closely monitoring the emerging data and evidence on COVID-19 and, after thorough consideration, we are now confident enough to recommend this new measure.” No link to the “emerging data and evidence” is provided.

Some were quick to point out that anosmia had been a well-established symptom of COVID for months before the government’s announcement. Indeed, the World Health Organisation listed it as a “less common symptom” as of 17 April, with US agencies following suit soon after.

Important questions are raised. What evidence supports this additional symptom? When did this evidence come to light? Is it possible to be infected with coronavirus and have only this symptom? How common is [acute] anosmia in the absence of coronavirus?

The emerging evidence base for anosmia and COVID-19

We have been collating the evidence on symptoms of coronavirus/COVID-19 over the past few months. We have focused on people with confirmed coronavirus infection, which has predominantly meant people who have been hospitalized and tested for the virus. In our last update, on 29 March, we identified the largest available systematic review of studies that looked at symptoms. The most commonly reported symptoms in these studies were fever (81-88%), cough (66-71%), and fatigue (44-60%). Anosmia was not identified in any of the studies included in this systematic review. The reviewers searched only for evidence published up to 25 February 2020.

Our colleagues specifically looked at the evidence for anosmia in COVID-19 up to the 23 March and found it to be “limited and inconclusive”. The first report mentioning anosmia that they found was a pre-print (non-peer-reviewed) report of a Chinese study, posted on 25 February, reporting a 5% prevalence.

Since then new reports have linked loss of smell and taste with coronavirus infection. In our searches up to 18 May we have identified a total of 22 systematic reviews, three of which specifically address the evidence of anosmia (and related conditions) and capture many of the latest reports.

The first, published on 13 April, included five reports in a total of 1556 hospitalized patients and identified other respiratory symptoms but found no reports on COVID-19 and anosmia or other olfactory disorders. However, the reviewers weren’t specifically looking for anosmia.

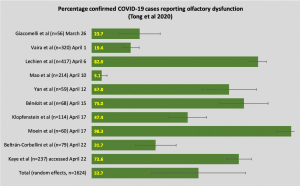

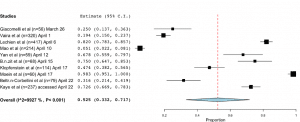

The second, by Tong et al and published on 5 May, included 10 reports in a total of 1657 participants (in any setting) specifically looking at olfactory dysfunction. Included reports were published between 26 March and 22 April from 9 countries; one report was related to Chinese participants, but none were from the UK. The pooled prevalence of olfactory dysfunction was 53% (95% CI = 30-75%, n=1624, Figure 1). Heteterogeneity was very high (I2 = 98.8%), with proportions ranging from 5% to 98% (see Figure 2). The authors also highlighted limited evidence from one study in which anosmia was present in 73% of 237 cases before the diagnosis of COVID-19 and was the presenting symptom in 27% of cases. The quality of the studies was judged to be poor overall, with self-reporting of symptoms and inclusion of people without a confirmed COVID diagnosis and a history of olfactory dysfunction before the COVID-19 outbreak, limiting confidence in the findings.

Figure 1. Proportion of participants reporting olfactory dysfunction from reports included in the systematic review by Tong et al (error bars = 95% confidence intervals). Reports are listed chronologically by date of publication.

A third review (unclear if it was systematic despite the title), published on 10 May, looked specifically at anosmia identified 31 reports, including the 10 reports in the second review above. Presentation of the data narratively makes it difficult to summarize the findings, and the authors gave no consideration to quality or heterogeneity. There were also citations missing from the reference list making it difficult to verify the accuracy of the reported data.

That said, the review states the inclusion of four reports from the UK (only 3 can be verified), including cross-sectional data from a pre-print of an ongoing symptom surveillance survey that reports a loss of smell and taste in 59% of 579 people self-reporting as positive for COVID-19. The corresponding rate in 1,123 people reporting negative for COVID-19 was 19%. These data have subsequently been peer-reviewed and revised, with 65% of 7,181 positive cases and 22% of negative cases reporting loss of smell or taste. Limitations of these data include non-random sampling, the self-reported nature of the outcome and exposure, the cross-sectional design and the effect of media coverage on responses. To their credit, the authors assessed the potential impact of this issue and found it may have influenced UK responders.

Figure 2. Pooled prevalence for olfactory dysfunction in Tong et al, demonstrating very high heterogeneity.

Summary

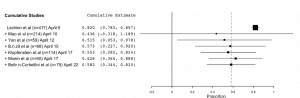

The evidence for anosmia as a symptom of COVID-19 started to emerge in late February and was restricted to Chinese populations. From late March, reports from countries outside China started to emerge and reported anosmia and loss of taste and smell as a symptom in people with COVID-19. A large, peer-reviewed report from UK and US community settings published in mid-May indicates that almost two-thirds of positive COVID-19 self-reported cases report a loss of smell or taste compared with a quarter of negative cases. An extremely cautious re-analysis of the data in Tong et al shows anywhere from 30% to 80% of confirmed COVID-19 cases reporting loss of smell or taste by mid-April (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cumulative meta-analysis of the proportion of confirmed COVID-19 cases reporting olfactory dysfunction from six reports included in Tong et al. This analysis needs to be interpreted cautiously given the presence of very high heterogeneity.

One of the potential negative impacts of the addition of acute loss of smell or taste to the list of symptoms that indicate self-isolation is the potential number of false-positive cases. Olfactory disorders including acute anosmia frequently occur with common colds and influenza. There are likely to be many people who will display symptoms but do not have coronavirus.

The current evidence base is predominantly of poor quality, due mainly to the retrospective and cross-sectional nature of the included study designs. Ongoing studies using symptom tracking in healthy users to prospectively track symptom development are needed to reduce uncertainty. Such studies should also indicate when the presence of anosmia occurs in relation to other symptoms which will be critical in helping to reduce the number of false-positive cases.

About the author: David Nunan is a Departmental Lecturer and Senior Research Fellow, Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences and Director of the Post Graduate Certificate in Teaching Evidence-Based Health Care

Acknowledgements: The author is grateful to Jeffrey Aronson and Helena Nunan for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this commentary represent the views of the authors and not necessarily those of the host institution, the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. The views are not a substitute for professional medical advice.